Mansha Mirza, Mustafa Rfat, Abigail O. Akande, Alison Foura, and Monika Gross

Introduction

Economic integration of incoming refugees is an important policy objective of the US Refugee Resettlement program. This policy objective cannot be realized without including refugees with disabilities, a group that is often overlooked in economic and labor policies and programs.

Refugees with disabilities, like everyone else, desire opportunities for economic integration, which includes finding and sustaining gainful employment, income security, financial self-sufficiency as well as opportunities for entrepreneurship, career development, and higher education.

Using data from the 2020 Annual Survey of Refugees (Urban Institute, 2024), this research brief summarizes: employment and labor force participation rates for refugees with disabilities, their participation in job training programs and educational opportunities, and the common employment barriers they encounter. Personal testimonials from refugees with disabilities are also included to shed further light on these topics.

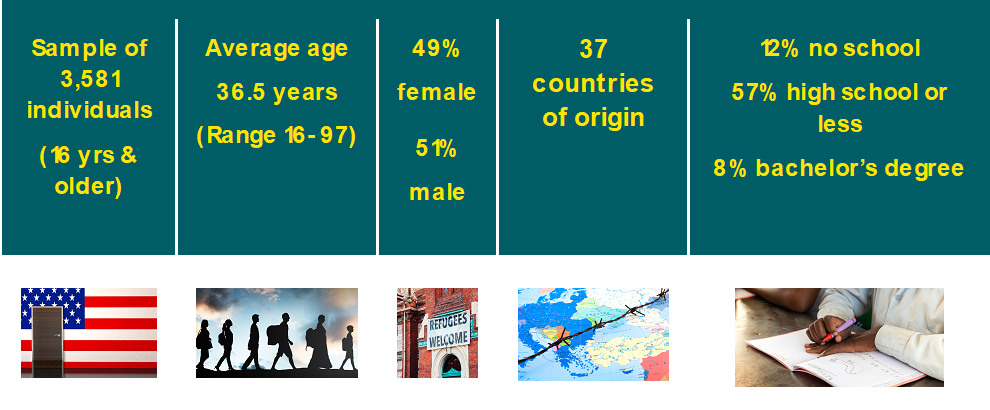

Data Source: 2020Annual Survey of Refugees Public Use Data File (Administration for Children & Families)

- Only source of national data on refugees’ economic integration.

- Target population includes refugees entering the U.S. between FY 2015 and FY 2019, inclusive, aged 16 years and older.

- Administered in 20 languages, including English, covers 77% of the FY2015-2019 refugee population1.

- Response rate 17%

Refugees with Disabilities

585 (16%) individuals reported ‘sickness or disability’ as a challenge in their job search and were identified as being a person with a disability(ies).

Economic Integration

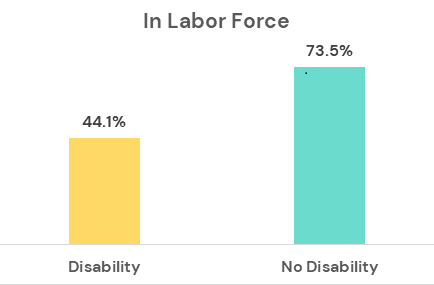

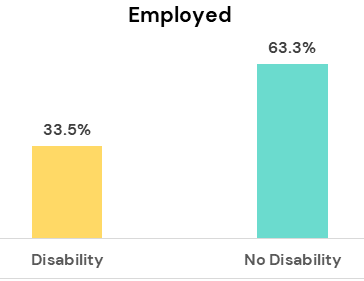

Of those with a disability (n=585), 44% reported being in the labor force (i.e. employed or unemployed and looking for employment).

The employment rate of refugees with disabilities was nearly half the rate for refugees without disabilities. This rate is also lower than average employment rates for working-age disabled women and men in the US, 36.1% and 38.2% respectively (Andara et al., 2024).

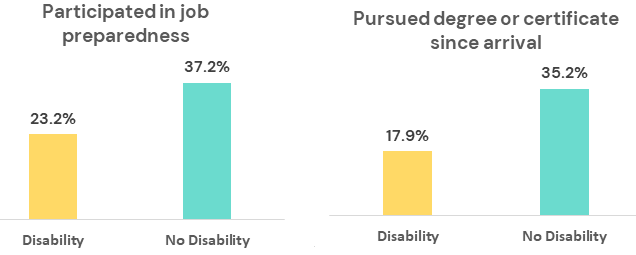

Refugees with disabilities were less likely to participate in job preparedness programs and pursue further education since arrival.

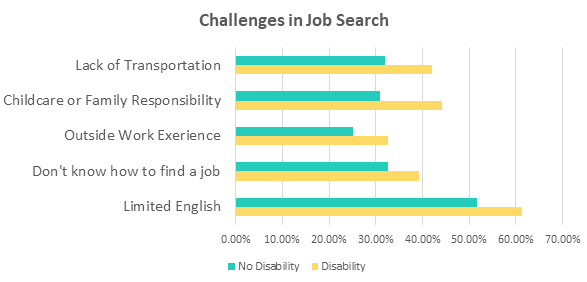

Refugees with disabilities were more likely to report challenges in finding work such as transportation, lack of prior work experience, lack of information, and limited English proficiency.

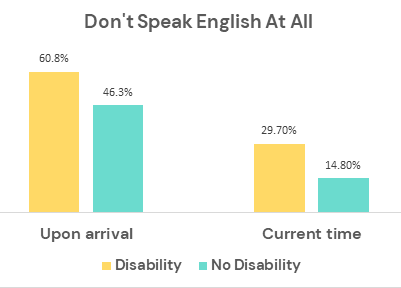

Limited English proficiency was the most common barrier to finding employment for refugees with and without disabilities. Refugees with disabilities had significantly higher (p<0.001) language needs upon arrival in the US compared to refugees without disabilities.

While English proficiency improved with more time in the US, the gap between refugees with and without disabilities appeared to persist over time.2

In summary, refugees with disabilities have lower employment and labor force participation rates compared to refugees without disabilities. They are also less likely to participate in job preparedness and educational programs and are more likely to report employment challenges. The following testimonials3 shed further light on these issues through first-person accounts of refugees with disabilities.

Personal Testimonials

“We do not know English and we don’t know about laws, and they bring us and tell us go and work. They don’t help us with education, so we need to prepare ourselves.” – Salih, middle-aged man with psychiatric disability, living in the US for 8 years

“There needs to be a good assessment, in the beginning to help us find jobs that will not worsen our health. We need some kind of internship-type opportunities, in the beginning, to improve our language and understand the labor world.” – Abbas, elderly man with physical disability, living in the US for 26

”They [rehabilitation counselor] didn’t want me to do nursing. So, they said…, I will pay for social work, but that was not what I wanted to study. They [rehabilitation program] did not pay for my education…. They did not help me; they were racist against me. [Interviewer asks, “Can you tell me more about that?”] So, first of all, they did not want to help me, they gave me a difficult exam, I could not pass because I could not understand the whole exam, and … whenever you go there [Rehabilitation office] they were not welcoming like they were not happy to see me.” – Songul, young woman with psychiatric disability, living in the US for 18 years

“[VR staff] tried their best to help me… they also tried to encourage me to attend school, but I could not obtain my diploma [from Iraq]. However, there was a worker who did not believe what I was telling him…the worker made me feel like he was tired of seeing me asking for help. I have my own dignity whenever I see I am not being respected and appreciated, I will not stop there. But other workers were kind to me.” – Abbas, elderly man with physical disability, living in the US for 26 years

“Their [coworkers’] attitudes toward me were different…I couldn’t tell [my manager] because I was shy…. At some point, they laid me off …They did not care. I could only survive one year in my first job; my health became worse…. I had to leave my job and was unemployed for a couple of years…’

– Abbas, elderly man with physical disability, living in the US for 26 years

These testimonials highlight multiple barriers to economic integration for refugees with disabilities. These barriers include lack of education and employment supports, negative experiences with vocational rehabilitation services, employment discrimination and lack of workplace accommodations.

Action Steps

Refugees fleeing persecution and hostile living conditions in their country of origin come to the US seeking safety, security, and the right to a dignified life. Opportunities for economic integration and participatory citizenship are fundamental to refugees’ dreams and aspirations for building a better life in the US. Economic opportunities create pathways toward self-sufficiency for individual refugees, revitalize local economies, and foster inclusive and diverse communities. Therefore, it is imperative that all refugees be afforded economic opportunities.

This research brief summarizes findings from quantitative and qualitative research, which together underscore gaps in economic integration of refugees with disabilities in the US. To address this gap, a concerted effort is needed across all levels of governance and service systems including:

- Department of State, the Office of Refugee Resettlement at the federal level

- State Refugee Coordinators and the Division of Rehabilitation Services at the state level

- Refugee resettlement agencies and disability service organizations at the local level

To this end, specific action steps are identified below.

| Improving Employment Opportunities and Outcomes |

| Designate funding to multisectoral programs that bridge refugee and disability service systems (i.e., to support reasonable accommodations, referrals, staffing, and related resources). |

| Connect newly arrived refugees with disability service providers, vocational rehabilitation counselors, and Centers for Independent Living. |

| Build capacity within state vocational rehabilitation offices to provide culturally and linguistically appropriate services. |

| Build capacity within refugee resettlement agencies to effectively define and recognize disability and to support educational and employment opportunities for refugees with disabilities according to the Americans with Disabilities Act. |

| Assess disabled refugees’ skills, interests, and prior work experience to match them with potential job opportunities. |

| Ensure that ESOL classes are accessible for refugees with disabilities (e.g. physically accessible classrooms, large print handouts, adaptations for students’ learning needs and accommodations). |

| Offer trainings, resources, and expert consultation related to disability awareness and inclusive education for ESOL volunteers and teachers. |

| Designate funds for accessible job training and entrepreneurship programs for refugees with disabilities. |

| Gather systematic data on the economic integration of refugees with disabilities e.g., employment status (full-time, part-time, integrated, supported, self-employment), job retention, job satisfaction, income security etc. |

| Integrate standard assessments to identify disability within the pre-resettlement documentation process (consider tools such as American Community Survey disability set questions, Washington Group Short Set on Functioning) |

The above recommendations represent important action steps needed to fulfill the promise of a better life for refugees with disabilities in the US; a promise that recognizes their right to equal opportunities, honors their hopes and aspirations, and leverages their skills and talents in pursuit of individual self-sufficiency and societal advancement.

Cited Sources

Urban Institute (2024, May). 2020 Annual Survey of Refugees. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 2024-05-17. https://doi.org/10.3886/E195403V2

Andara, K., Neal, A., & Khattar, R. (2024, February) Disabled workers saw record employment gains in 2023, but gaps remain. Center for American Progress. Center for American Progress (February, 2024). Retrieved from: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/disabled-workers-saw-record-employment-gains-in-2023-but-gaps-remain/#:~:text=Strikingly%2C%20when%20people%20of%20all,with%20disabilities%20was%2022.5%20percent.

Foot Notes

[1] Countries of origin include Armenia, Afghanistan, Belarus, Bhutan, Burma, Burundi, Colombia, Cuba, DR Congo, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Malaysia, Moldova, Nepal, Russia, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tanzania, Thailand, United Arab Emirates, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Zambia

[2] Average number of years between ‘arrival’ and ‘current time’ was 3.3 years, standard deviation = 2.7 years

[3] These testimonials are drawn from the second author’s dissertation research with 37 refugees with disabilities from seven countries of origin and dispersed across 13 states. Please see the appendix for details.

About the authors

Mansha Mirza is a Professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy, University of Illinois Chicago.

Mustafa Rfat is a Ph.D. student in Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis.

Abigail O. Akande is an Associate Professor of Rehabilitation and Human Services at Penn State University – Abington College.

Alison Foura is an Occupational Therapist and Owner of Progressive Pediatric Therapy, LLC.

Monika Gross is an Alexander technique specialist and the Executive Director of The Poise Project, a nonprofit in Candler NC.

All authors are members of the Refugee Empowerment Task Force within International Interdisciplinary Special Interest Group, American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine for offering the platform and opportunity to develop this issue brief. We are also grateful to Jamilah Alqahtani, Hassan Ahmed Ali and Qusay Hussein for their contributions. Special thanks to Dr. Yolanda Suarez-Balcazar for her insightful feedback on early drafts of this report.